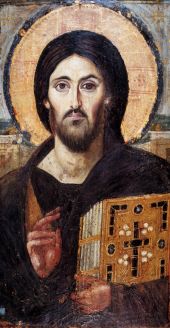

Christ Pantocrator, Mt. Sinai, 5th-6th Century A.D.

In modern day ecumenical efforts made by most unity-driven Christians, the following topic either goes half-defined or altogether overlooked. Yet, sadly, it is one of the most misunderstood and most off-putting parts of Catholicism to most Protestants. The topic of Icons and Sacred Images is something very near and dear to my heart. It was actually the last thing I had to reconcile before becoming Catholic – thinking before that it was wrong and completely idolatrous. Now, however, I see it as one of the most relevant elements to an authentic Christianity… one that finds its roots, as all parts of Catholicism do, in God Incarnate.

Introduction to Sacred Images

Utilizing images to facilitate Christian worship is part of an ancient formula. Among the broader Protestant realms of Christianity, this formula has been revoked. By employing the motif of the Incarnation, I intend to demonstrate the relevancy of Sacred Image usage for those parts of Christendom that now consider it archaic and useless. I will explore the influential studies of St. Athanasius and St. John of Damascus, as well as more contemporary academic works, to shed both historical and philosophical light on the ancient practice, its theological framework, and the misconceptions associated with its observance.

In most cases, discussions like these necessitate a clear and distinct audience to be directed towards. Yet, to do so would prove impossible. Given the nature of most Protestant traditions, which often describe the Church as an invisible and spiritual communion of believers from every denomination, one cannot seek out a tangible party to have this dialogue with and avoid excluding another. The only thing that consistently and visibly unifies Protestant traditions, in my humble opinion, is that they are not Roman Catholic. All one can do then is broaden those traditions opposite of one’s own into a single category of Christian faith, or in this case: those who have no faith in the Roman Catholic Church. So, the audience this thesis calls forward is a mixture of both my Catholic brethren, who need an internalized knowledge on these matters, and those of my Protestant brethren, who object to Sacred Images used in worship.

In Salvation history, the Incarnation of God was integral to the grounds through which we as the people of God attain Salvation. The Incarnation, as most well know and profess, was wrought for the sake of man to the glory of God and was realized by the Word of God becoming flesh in the person of Jesus of Nazareth. Consider the sheer complexity and effectually profound nature of this most Sacred of mysteries. Let us not only grow in intellectual discipleship, but let us also stand in awe of the power of God and His self-giving act of Incarnate Love.

God, by His nature, is eternal and infinite. He has no beginning. He has no end. He dictates the transcendent and the sensorial. He created us. He dictates the makeup of our reality. What is most real to us? How can we as finite and limited and inherently flawed beings realize what is real? As implied in the word “sensorial,” what is most real to us naturally as a component of our humanity is realized in our senses; in this case, our sense of sight.

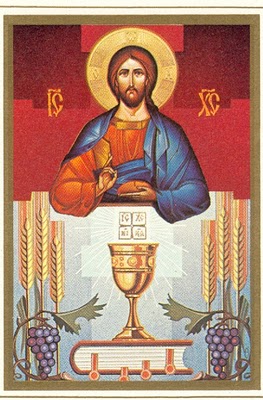

In Catholic and Eastern Orthodox sanctuaries you cannot go far before seeing iconic triptychs, statues, crucifixes, and other visual depictions of Christ and the Saints. Since the earliest recorded periods of Christian history, Sacred Images have decorated places of worship and Christian households to make worship an experience of the senses and the mind, in perpetuated understanding of the Sacred Image: Jesus Christ. This often-challenged reality has been a consistently implemented one, which has proven itself an essential element to Catholic and all Orthodox Christian traditions throughout the centuries.

The Virgin of Guadalupe

Upon looking back to when I first became aware of Christian Orthodoxy visually, that is, as seen in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions, I remember being viscerally offended. While finishing homework after school one day, I caught the tail end of a News special that showed a group of elderly women crowding around a particular depiction of the Virgin Mary known as The Virgin of Guadalupe. As the footage progressed, one after one each woman kissed the image and appeared to be praying to it. To my young Evangelical Christian slash Jewish perspective this was heretical. What these women were doing was idolatrous and completely unbiblical. Yet, as I was informed soon after, these women were practicing a Christian tradition that historically outlasted my own. This surprised me. I wondered how these women and other Catholics could be so blind to this obvious sin, and for so long. This simple after school moment became integral to the trajectory my life has taken. It, in more ways than one, led me to the Faith tradition that I am a part of now. It was this chance moment that proved causal to my desire for knowledge of Church History–which ultimately led me to the Catholic Church.

Iconoclasm

The Iconoclasm

The year was AD 726. The one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church was in full and corporate communion between the geographic regions of the East and the West. Six ecumenical Church councils had been previously conducted, each one with the purpose of defining fundamental and unifying doctrine and of combating and protecting against heresy (Catholic Encyclopedia). It was in this year that the Byzantine Emperor, Leo III, ordered images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the Saints destroyed throughout the Byzantine Empire (John of Damascus, 7). This event, which formally lasted about a century long, became known as the Iconoclasm. Though history is unclear as to what finally spurred Leo into political action, we do know that he justified his edicts by declaring that the usage of images was: idolatrous, in contravention of the second commandment and a stumbling block to the conversion of Jews and Muslims (Louth, 7). Now, it should be said here that the historical context of the Byzantine Empire at this period was a bit complicated. Leo’s imperial reigns on the Church were starting to loosen and he was aware of the “drain of manpower” at hand (Anderson, 27). Scholars agree that at this time the political climate of the Iconoclasm, “involved more issues than an attack on the…practices connected with images” (Anderson, 27). These issues, incidentally, were the burden of the Christian Monks.

The most faithful proponents and defenders of Sacred Image usage at this time were the monastic religious, who began to really take visual and corporal shape in the Latin and Byzantine parts of the Church during the 8th century. The Eastern monks were often targeted by Byzantine Imperial rule because, by Church and Imperial law, they were immune to taxation and were therefore an economic burden and threat (Anderson, 27). Because of Leo’s attacks, the monks frequently opposed the imperial will. This was the case especially when the Iconoclast edicts claimed to be “an attempt to purify a religion which had become sullied by superstitions and magical practices” (Anderson, 27). So, we may be safe to say here that perhaps it was the monastic religious community of the Byzantine Empire that was sought out by Leo for reasons unrelated to the Iconoclasm and then put on trial in an attempt to redeem Leo’s power over the Church in his empire.

The Objections

Now let us consider the Protestant objections to Sacred Images; those of which do not differ much in substance from that of the Iconoclasm’s. These objections are relevantly coupled as: (a) Sacred Images are a direct violation of the Second of the Ten Commandments and (b) are therefore causally idolatrous. The Second Commandment reads, “You shall not make for yourself an idol, or any likeness of what is in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the water under the earth. You shall not worship them or serve them; for I, the LORD your God, am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children, on the third and the fourth generations of those who hate Me, but showing lovingkindness to thousands, to those who love Me and keep My commandments” (Exodus 20:4-6, NASB). As anyone can see here, there is more than just one commandment in these verses. In fact, throughout the Decalogue, there are more than just Ten Commandments. Yet, traditionally Judaism and Christianity have grouped what looks like more than ten ordinances into ten categorical commandments of moral law. For instance, in the second commandment we see 4 ordinances:

1) You shall not make for yourself an idol

2) or any likeness of what is in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the water under the earth

3) You shall not worship them

4) or serve them

These ordinances are interrelated and interdependent within the categorical context of idol worship, which is why the Church Fathers saw it fit to group them as one of the Ten Commandments (St. John of Damascus). The first ordinance is the root of the rest. It sets up the context in a strict sense. The sense is so strict that it is what makes each of the ordinances in the Second Commandment compatible in the one category they have been traditionally grouped in. Usually, when this verse is held up against Sacred Images, it is divided up rather than maintained in its categorical context. As was the practice of Leo in the 8th century, and currently in many Protestant Christian circles, the Second Commandment is often limited to its first two ordinances when utilized in this discussion,

1) You shall not make for yourself an idol

2) or any likeness of what is in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the water under the earth.

So, it would seem that the Most High banned any kind of image or likeness from being made, not just idols. Yet, as we see in scripture He did just the opposite. The God that gave this commandment also commanded graven images of Cherubim onto the Ark of the Covenant (Exodus 25:18 NASB), images of pomegranates and cattle to decorate the Temple (1 Kings 7 NASB), and a bronze serpent on a pole to be looked upon for healing in the desert (Numbers 21:5-9 NASB, John 3:14-15 NASB). So, at this point we must ask ourselves: is God a God of contradiction? No, He is not. God is a God of context.

Dividing up the Second Commandment causes obvious contextual problems for the first part of the Protestant objection. Again, for the Israelites, the context of each ordinance of the second commandment was and is idolatry (worshipping that which is not God as God). So, for this objection to be legitimate, we Catholics/Orthodox would have to be “worshipping and serving” the images we make as if they were God or gods. Yet, as St. John of Damascus explains, we do not.

St. John of Damascus

St. John of Damascus

St. John of Damascus, the Doctor of Sacred Art, as is formally the title given to him by the Catholic Church (Catholic Encyclopedia), was at the Church’s vanguard against the Iconoclasm and wrote three treatises on what he calls, “the divine images” (St. John of Damascus). In sum, he roots his arguments in the Incarnation of the Word of God made flesh: “Who first made images? God himself first begat his Only-begotten Son and Word, his living and natural image, the exact imprint of his eternity; he then made human kind in accordance with the same image and likeness” (St. John of Damascus, 103).

The orthodox practice of utilizing Sacred Images in worship does not, as result, causally implicate the sin of idolatry. There is a form of worship that comes about when engaging images religiously, and this form is seemingly directed towards the image. Yet, this is not idolatry or a form of meditative polytheism. It is a form of honor, directed at whom and what the image ultimately depicts.

The honor given to Sacred Images is a form of veneration. “Veneration (bowing down) is a symbol of submission and honor” (St. John of Damascus, 27). Scripturally and linguistically there are two forms of veneration. The first form, as St. John describes it, “is a form of worship, which we offer to God, alone by nature worthy of veneration” (St. John of Damascus, 27). This is the veneration that contextualizes the Second Commandment. This is not, however, the form of veneration that contextualizes Sacred Images.

The second form of veneration, which is the form offered to Sacred Images and to the Saints in Heaven, “is the veneration offered on account of God who is naturally venerated, to his friends and servants, as…Daniel venerated the angel; or to the places of God, as David said, ‘Let us venerate in the place, where his feet stood’” (St. John of Damascus, 28). We can see this form of veneration in verses like Proverbs 31:30 where King Solomon says, “Charm is deceitful and beauty is vain, but a woman who fears the LORD, she shall be praised” (NASB). The word “praised” here does not mean to worship a woman akin to this description as God or a god, but to celebrate her as one who fears God, and therefore as one who directs others in her fear towards God by her example. Furthermore, the two forms of veneration can be narrowed down to even simpler degrees. When we worship God, we directly venerate Him according to His nature. When we honor the Saints and Sacred Images, we indirectly venerate God on “account of” His nature–which creates and renews Man in the Divine Image of His Son.

St. John applies this structure to the practice of image veneration by saying “should I not therefore, make an image of the one who appeared for my sake in the nature of flesh, and venerate and honor him with the honor and veneration offered to his image?” and in the same manner, “should I not make images of the friends of Christ, and should I not venerate them, not as gods, but as images of God’s friends? For neither Jacob nor Daniel venerated the angels who appeared to them as gods, neither do I venerate the image as God, but through the images of his saints I offer venerations and honor to God, for whose sake I reverence his friends also, and this I do out of respect [for them]” (St. John of Damascus, 102).

Introduction Incarnate

Taking a step back even further in Christian history, we find the ultimate precursor to Sacred Image usage in worship: the Incarnation. Aside from the New Testament authors and their studies on the nature of the Incarnation, the Church Fathers really grasped this facet of Christology in a significant way.

In the 4th century A.D., there was a Greek-Alexandrian Patriarch named Athanasius who composed a doctrinal epistle called On the Incarnation of the Word. The reason for his written work was to confront and uproot the heresy of Athanasius’ age: Arianism. Arianism presupposed that there was a time when the Son of God, “once was not” (St. Athanasius, 19). The originator of this teaching, an Alexandrian presbyter named Arius, based his related homilies off of the assumption that Christ had one nature, not two in a hypostatic union as later defined by the first Nicene council. According to Arius, God the Son was not “eternally begotten of the Father” and had actually entered His original existence on the day of His Virgin birth (Athanasius, 2). This presented a dilemma that was obviously incongruous with scripture and the traditional teaching of the Church. So, St. Athanasius took it upon himself to write his succinct yet powerful epistle, On the Incarnation of the Word, as a point of putting face to the intent of God in the Incarnation and why the nature in which it occurred was necessary.

St. Athanasius

St. Athanasius

In terms of necessity, Athanasius had two main arguments for the Incarnation. Both of his arguments pertained to “the divine dilemma,” that being the fall of man, and “the divine solution” that being the Incarnation of Almighty God. The essence of the first argument involved the corruptibility of humanity fallen. Since the original sin of Adam, humankind was stripped of its divinely intended incorruption and was given over to the powers of death and sin. Being that our originally created nature was rooted in God’s Image, that which is incorruptible and good, the self-giving love of God was put into play for the reconciling of our now corrupted image. Athanasius resolves this argument by saying, “for this purpose, then, the incorporeal and incorruptible and immaterial Word of God entered the world” so that mankind would have the opportunity to return to their intended state of incorruption (St. Athanasius, 33).

St. Athanasius’ second argument engages the loss of understanding of the nature of God amongst men, which was also an effect of Adam’s sin in the fall. This type of argument is often misconstrued as a semi-Gnostic one because it involves the overarching theme of the need for understanding. However, contrary to Gnosticism, this argument points to our understanding as being only a road map back to God and not an end in and of itself… which is exactly what Sacred Images do in effect. They are not “ends” but modes of worship, which perform as roadmaps pointing towards the only One deserving of our worship. If this is idolatry and therefore evil, then by nature all modes of worship are evil since they all point our focus towards God in an indirect way. In the words of St. John of Damascus, as he says repeatedly throughout his treatises on images, “Either therefore reject all veneration or accept all of these forms with their proper reason and manner” (St. John of Damascus, 28). Athanasius proposes, “What then was God to do? What else could he possibly do, being God, but renew His Image in mankind, so that through it men might once more come to know Him? And how could this be done save by the coming of the very Image Himself, our Saviour Jesus Christ?” (St. Athanasius, 41).

The Crucifixion

The Crucified Christ

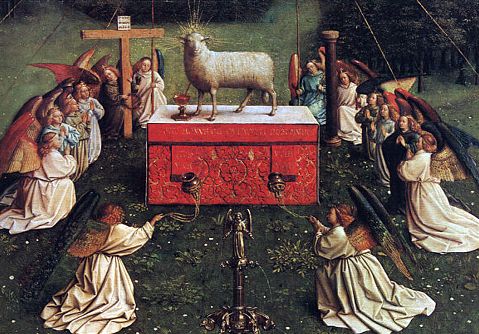

So, according to St. Athanasius, God needed to renew His image in mankind that we might regain our native state of incorruption and come to know Him once more. This, God accomplished in the life, death and resurrection of His Son, Jesus of Nazareth. When it comes to the death of Jesus, no image is more familiar to the Christian’s visual pallet than the Crucifixion. Consider the aesthetic of this image. Consider the aesthetic of God in the flesh being crucified. Nothing is more of a conceptually driven image of God’s love than this. Think of how we would perceive, from a Sacred Image, God’s love in the sacrifice of Christ if He were sentenced to another kind of death. Say, death by poison or death by the sword. There is an inherent depth to this very visual, very purposeful, part of God’s plan. The arms of God: stretched, welcoming. His hands: opened with the same loving intent, to catch and cast out our sin. His Body: hanging upright and securely fastened to His Passover, just as secure as His resolve to ransom us from our corruption. Consider the Cross itself. As G.K. Chesterton notes in his book Orthodoxy, the vertical and horizontal lines of its shape are met with a perpendicular contradiction in the structural middle–a “paradox” (Chesterton, 13). When we gaze upon where the beams meet and cross we are reminded that Faith is a paradox. It is a mystery that ultimately transcends us. It is a mystery that causes our complete reliance on God’s providential plans for each of us even though we could never fully comprehend their full scope. This Sacred Image is so crucial to our Faith now as it was to those who witnessed it first-hand. Additionally, since we today were not there to witness the Crucifixion let alone the Incarnation first hand, a Sacred Image like this one includes us in that moment. It gives us glimpses into how it must have felt to see “the exact imprint of God’s image” carry out the Divine Solution. Of course, it could never be to the same extent as the actual historic occurrence, however all Sacred Images function in a surrogated extension which does not replace the actual, but furthers its sensorial reality.

Throughout this post, I have included images. It seems to me that this thesis would prove irrelevant if I did not do so, and that it would ultimately fail. Visual association is what the Church, really God, has deemed as crucially important to His saving work and our understanding of it. Why would it not be crucially important to an argument that seeks to renew the rational and spiritual understanding for why Christianity had Sacred Images in the first place? If I had not included images, in my humble opinion, it would be tantamount to the Iconoclasm’s discrediting of such images. Once again, I would be stripping these “Divine Images” of their usefulness and ultimate purpose. Which was and is to redirect us back to God via our senses.

A Familiar Face

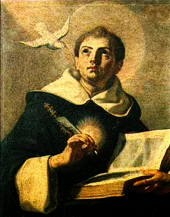

In addition to the arguments addressed previously, I would like to propose another in the same tone, yet requiring a farther stretching reach of Faith. One of the oldest Icons of Christ is the Christ Pantokrator. This image is depicted at the beginning of this post, dated between the late 5th to 6th century A.D., and shows the living Christ clutching the written Gospel and raising his right hand in blessing (The Sacred Image, 229). This Sacred Image of Christ is mostly used to decorate the inner domes of Eastern Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches, as if He were looking down upon us in perpetual blessing and reminder of the Gospel’s written and spoken message. What I would like to address here is the actual likeness of Christ; His hair, His beard, the bone structure of His face, His eyes, and even His expression. The whole visual likeness of Christ in this Sacred Image, and in other ones associated with Him, has a look of similarity across the board. Is this coincidence? I propose that it is not. I propose that Sacred Images of Christ and the Saints have another purpose altogether making their usage really worthwhile; and that is that these images retain a percentage of how the historic persons depicted actually looked. This could be argued either way and I do not present this empirically. Still, one must admit that the odds are there, since Sacred Images are so ancient. Who knows? Perhaps alongside the oral traditions meticulously preserved by the Apostles and their successors, there existed a maintained visual tradition of how Christ looked. And, inherently, maybe the Church kept this practice throughout the ages with the Saints as well. So, why avoid the possibility of seeing the face of Christ and His friends, our Mothers and Fathers in Faith, as they were when they paved the way before us?

Concluding Remarks

In conclusion, the orthodox sects of the Church have never allowed the worship of images of Christ and the saints, but the veneration or honoring of them. It was because of the teachings of St. Athanasius and St. John of Damascus that led the Church to her ongoing understanding of the nature of God and the nature of His incarnate Word. Which, epistemologically developed by the facilitation of Sacred Images—both Incarnate and hand-graven—in worship. In closing this post, I would like to leave a bit of wisdom from St. John of Damascus’ On the Divine Images. Found near the end of the first treatise, St. John says, and I will end with this,

“Of old, God the incorporeal and formless was never depicted, but now that God has been seen in the flesh and has associated with human kind, I depict what I have seen of God. I do not venerate matter, I venerate the fashioner of matter, who became matter for my sake and accepted to dwell in matter and through matter worked my salvation, and I will not cease from reverencing matter, through which my salvation was worked. I do not reverence it as God—far from it; how can that which has come to be from nothing be God?—if the body of God has become God unchangeably through the hypostatic union, what gives anointing remains, and what was by nature flesh animated with a rational and intellectual soul is formed, it is not uncreated.” (St. John of Damascus, 29)

Bibliography

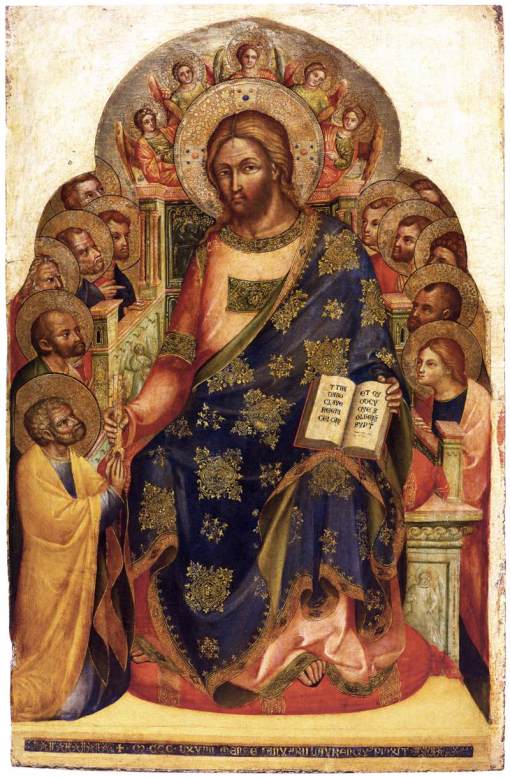

Anderson, Jeffrey C. “Byzantine Panel Portrait.” The Sacred Image East and West. Vol. IV. Chicago: University of Illinois, 1995. 1-302. Print.

Athanasius, St. On the Incarnation (De Incarnatione Verbi Dei). New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary, 1975. Print.

Catholic Encyclopedia. Catholic Church, 2000. Web. 2009. <http://www.newadvent.org/>.

Chesterton, G. K. Orthodoxy. Vancouver, British Columbia: Regent, 2004. Print.

Church., Catholic. Catechism of the Catholic Church with modifications from the editio typica. New York: Doubleday, 1997. Print.

John of Damascus, St. Three Treatises on the Divine Images (St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press Popular Patristics Series). New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary, 2003. Print.

The Sacred Image East and West. Vol. IV. Chicago: University of Illinois, 1995. 1-302. Print.

Venerate my sanctuary, says the Lord our God (Leviticus 19:30). Why should we? Well, first off, because He says so. It is His will. And it is our duty as His people, to follow His will. Yet, for those of us that need to understand why we need to obey Him before we obey Him (Lord, have mercy), in venerating God’s sanctuary, we worship Him. Honor given to a type passes to the prototype.

Venerate my sanctuary, says the Lord our God (Leviticus 19:30). Why should we? Well, first off, because He says so. It is His will. And it is our duty as His people, to follow His will. Yet, for those of us that need to understand why we need to obey Him before we obey Him (Lord, have mercy), in venerating God’s sanctuary, we worship Him. Honor given to a type passes to the prototype.